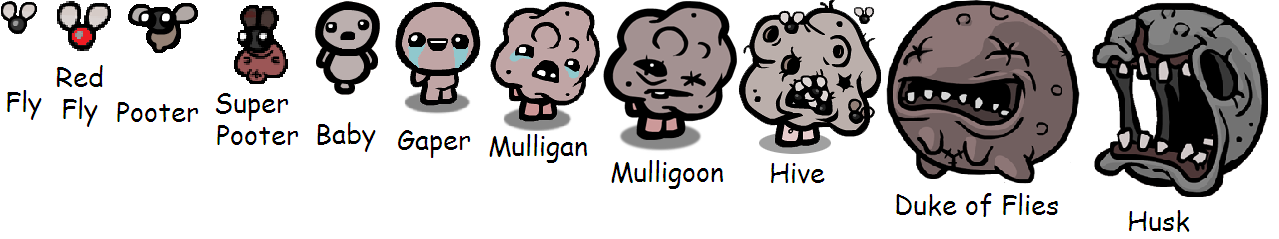

But there's another aspect to this game that was brought to my attention, and I'd like to talk about it today. That aspect is the change in appearance that you undergo as you go deeper into the basement. But before we can talk about that, we need to talk about the enemies of the game.

The game starts, and in the early levels, you are mainly pursued by things that are variations of your standard body type. For example, this is you:

Naked, weeping, but not altogether aesthetically unappealing. Now, compare this character model to the enemies from the first few levels, and you'll start to see something interesting happen.

Naked, weeping, but not altogether aesthetically unappealing. Now, compare this character model to the enemies from the first few levels, and you'll start to see something interesting happen.

Yes, there are a lot of bugs, spiders, flies, demons from Hell, all that as enemies, but a lot (maybe not most, but a significant proportion) of the enemies are just mutations of your character model. Now, this by itself doesn't really say much, but hold on, because there's more to talk about.

As you go deeper into the basement, you have item rooms crop up, and these item rooms, and the items in them, are the major means through which you can upgrade your stats. All the items you pick up from the item rooms are there to upgrade your speed, your tears, or to give you new abilities, like

As you go deeper into the basement, you have item rooms crop up, and these item rooms, and the items in them, are the major means through which you can upgrade your stats. All the items you pick up from the item rooms are there to upgrade your speed, your tears, or to give you new abilities, like

So what? Well, this tells you something about the enemies you're fighting. The enemies you're fighting are corrupted versions of someone like you. Perhaps brothers and sisters who have also escaped into the basement, and have picked up powerups themselves. Their abilities, to generate flies, to spit tears or blood, mirror those of your abilities, and their deformities mirror your own. There is no upgrade that comes without a physical cost, and these mutated enemies tend to show up at the beginning when they're still more deformed than you. But as you go deeper, the enemies devolve more and more into creatures from nightmares, and you sort of forget about the things that looked sort of like you but a little bit off. Until you get to the final boss,

When you encounter the boss of the game, something strange happens. It's you. Isaac is the final boss. But not strange, messed up deformed Isaac, regular Isaac. Contrast the random hodge-podge

When you encounter the boss of the game, something strange happens. It's you. Isaac is the final boss. But not strange, messed up deformed Isaac, regular Isaac. Contrast the random hodge-podge

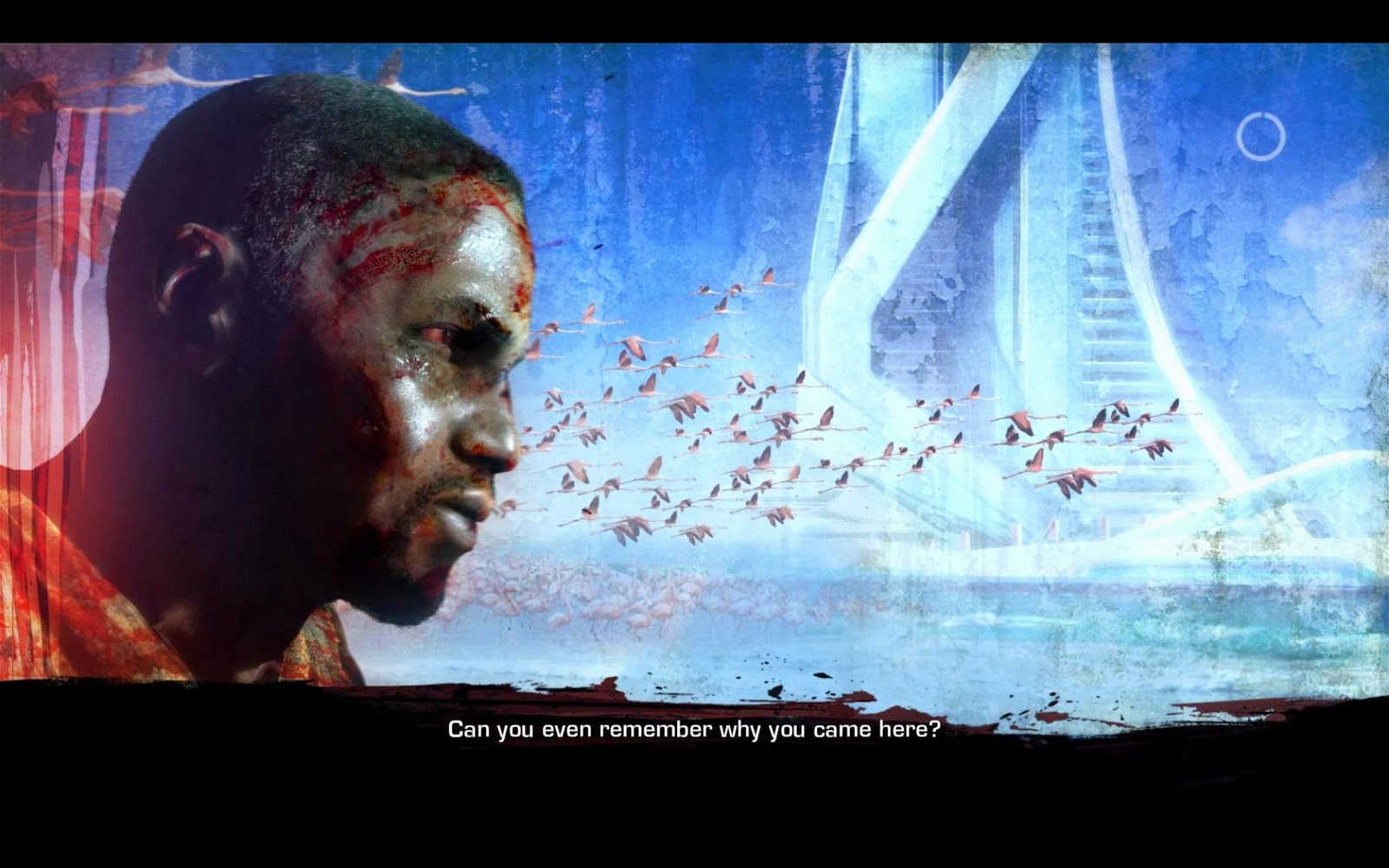

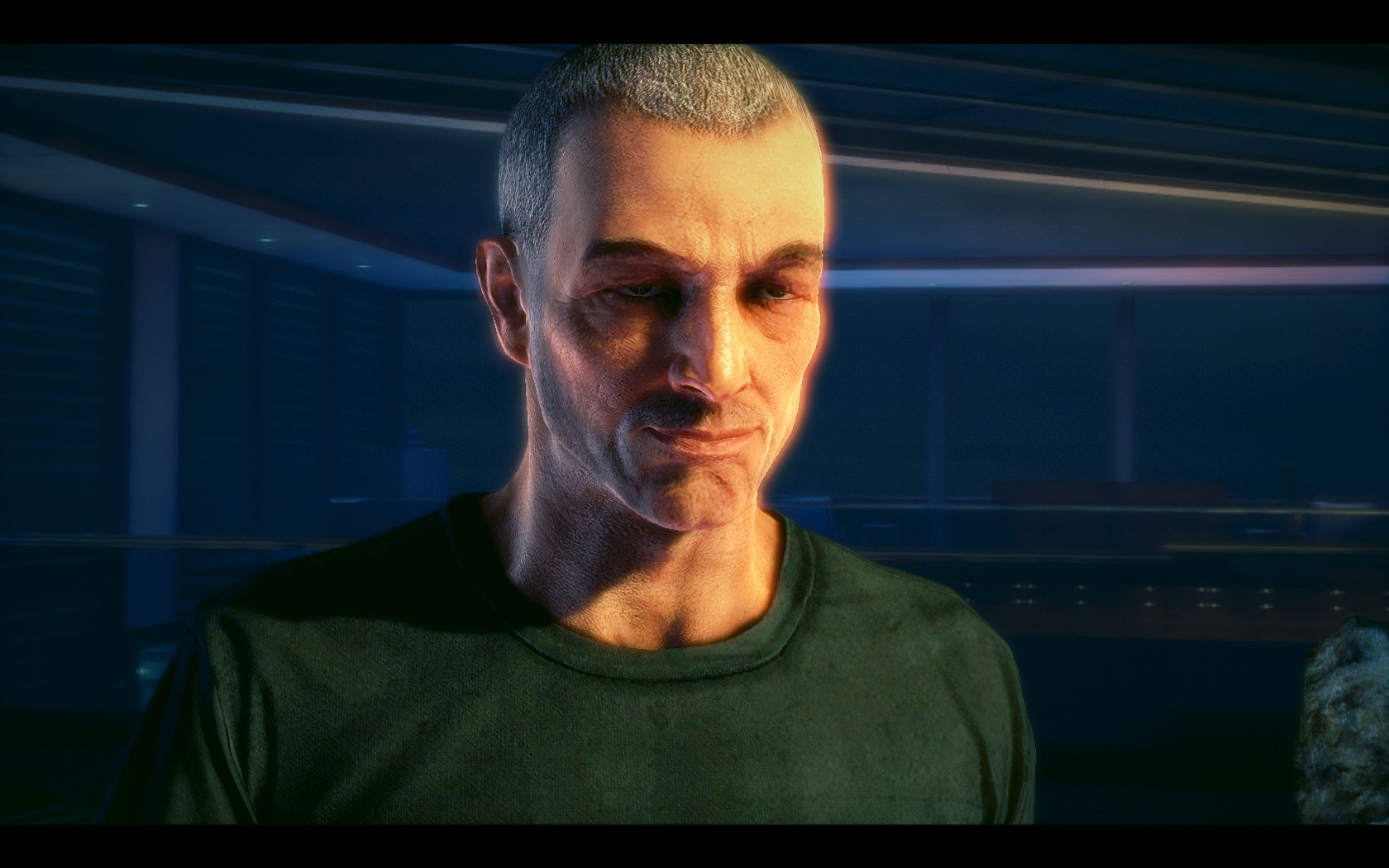

It's a lot like Bioshock in that regard. In Bioshock, you're the protagonist by virtue of being the player character, but you're on the same core level as the rest of the enemies you're fighting. They're all splicers, and from very early on in the game, you are too. You spend a generous amount of time

splicing, recombining your genetic code, which is the core problem that everyone else in rapture was dealing with too. They're no different from you, though you think you're all special and different and unique. And this is where the ambiguity kicks in. In neither of those two games are you out for a noble task, not really. You're into it for self-preservation, to survive and to progress. But the deeper you go, the more you turn into the monsters that you're fighting. As you splice in Bioshock, or pick up items in Isaac, they change you. All of a sudden, in Bioshock, you have charred flesh, or hornets all over your skin, or ice breaking through your knuckles, and it all seems normal, because it's what you have to do to survive. And it's what everyone else is doing to survive, too. Isaac, same deal. You can pick up powerups that will let you manipulate the flies, the spiders, vomit blood, fly, weep faster, and all those powerups mimic what you see in the enemies around you. They're twisted, and so are you.

If you pause and think about how video games work, you play the part of the hero, but why are you the hero? You certainly cause a bigger bodycount than anyone else. The number of things you break is huge, the bodies are stacked up like cordwood, there are explosions all over the place, and an awful lot of families have lost their dads. You're as spliced up and despoiled as the enemies you're facing. So what makes you the hero?

The fact that you're the character that you control.

This is the source of a lot of problems, and one that the Bible really does work hard to bust your chops on. You are the main character of your own story, and it's easy to see the rest of humanity as essentially being either disposible or at worst adversarial, mainly due to the fact that they're not you. This is how we work out who the heroes and villains are in our own lives, by viewing other people and asking if they're standing in the way of what we want to do or not. That's pretty much it. If you've ever wondered how it is that people can be engaged in terrible evil, can be involved with murder, rape, molestation, and so on, and all think they're good people? It's because like Booker Dewitt, like Isaac, heck, like Comstock, we are all the stars of our own show. And the people who are around us who stand in our way, they are our enemies.

But the first and greatest lesson of the Christian faith is to look at yourself, genuinely, and ask who you are. Ask if you're doing what you think people should be doing. Are you behaving in the way you sincerely believe other people should behave? If not, why not? It's the lesson that John the Baptist taught before the ministry of Jesus even began. It's the lesson that the prophet Nathan delivered to David, telling him that he was the one who was behaving in a way that he himself found to be abominable and deserving of death. In other words, when you get to the end of the binding of Isaac, and you find that you're corrupted, that you're not looking overly heroic anymore, you have a moment to pause for thought, and ask yourself what it is that makes you the hero.

For Christians, the only thing that we can cling to is Jesus, who offers us a chance to reset. To be forgiven. To look at our decisions, to look at how corrupted we are, and to fall on the one who has promised that he can restore us to the way things should be. Restore us back to where we knew people were always supposed to be. In the most roundabout way of explaining things, the only way out is to reset. To go back.

The deeper into the dungeon you go, the more corrupted you get, or you don't survive. Just like real life, the longer you're around, the more corrupted you get, the worse your decisions, until you come face to face with the realization that you are a long way away from how you believe people should live. So you have a choice. Pretend that you're doing well, and that everyone else is corrupt, or to fall on the mercies of Christ, who will protect, restore and renew you, washing away all those things you picked up, and returning you back to how you were at the beginning.